This story is part of an upcoming “History Around Every Bend” episode to be titled “1864: Chaos in the Mountains” which will explore a series of events that started at the beginning of that year and proceeded through November 1864, each of which was a cause-and-effect incident related to the next.

Friday, September 2nd, 1864 dawned as another humid, hot day – the last vestiges of summer held its grip on the peaks and hollows of the North Georgia mountains. Just 100 miles to the south, as September 2nd progressed, the last vestiges of the confederacy released its grasp in the fall of Atlanta, and the critical hub of the south fell to Sherman’s army.

Senses fully engaged, carefully, with stealth, twenty-seven-year-old Edward Callahan O’Kelley, a Union private in Company C of the 10th Tennessee Cavalry[1]Compiled Service Records, Company G, 10th Tennessee Cavalry (Union), Edward Callahan O’Kelley. Age 26, Enlisted 1/18/1864 for a period of 3 years in Nashville, TN. Mustered into service 2/27/1864. … Continue reading and his brother thirty-three-year-old John Pendleton O’Kelley plodded through the maze of mountain laurels near the Toccoa River. John was a rebel private AWOL from Company H of the 42nd Georgia Infantry CSA[2]Compiled Service Records, 42nd Georgia Infantry (Confederate), John Pendleton O’Kelley. Muster Date 3/4/1862;’ 5/15/1862 Disabled/Rheumatism; 10/2/1863 Absent, Unfit for Service.

Copied from

Aska Road – Toccoa Rapids Roadside Marker,

original image owned by

Bob Barton, descendant of Edward O’Kelley

Edward Callahan O’Kelley himself had at one time fought for the rebel cause as a private in Company G of the 24th Georgia Infantry[3]Compiled Service Records, 24th Georgia Infantry (Confederate), Edward Callahan O’Kelley. Enlisted 8/24/1862 in Whit Co., GA by Capt. Leonard. Left sick in Winchester, VA. 10/19/1862; Admitted to … Continue reading. He was wounded at 2nd Manassas in August 1862 and in the aftermath had switched sides, joining Federal forces in Nashville in January 1864. “We were always told as was passed down through my aunts and uncles that he was not happy with how his rebel company treated the civilians–pillaging and raping”, said Bob Barton, of Marble, North Carolina, O’Kelley’s 3X grand nephew, “they weren’t raised that way.[4]Bob Barton interview by Steve Procko; June 2018“

Since he was a former soldier in the confederate army, Edward O’Kelley signed a loyalty oath to the United States. There were several variations of this oath, but they all carried the same message–this would have likely been what Edward C. O’Kelley signed when he enlisted in Nashville at the Provost Marshall’s office:

I do solemnly swear, in the presence of Almighty God, that I will henceforth faithfully support and defend the Constitution of the United States thereunder, and that I will in this manner, abide by and faithfully support all Laws and Proclamations which have been made during the existing Rebellion with reference to Emancipation of Slaves–”SO HELP ME GOD”.

Sworn to and subscribed before me, at Nashville, Tenn. this 18th day of January, 1864.

Provost Marshall

The two brothers were headed north towards Union lines at Cleveland, Tennessee after visiting their mother Nancy Chastain O’Kelley who lived in White County, Georgia. The O’Kelley’s had likely spent the evening of September 1st with their Chastain relatives, of whom there were many, living in Fannin County near the community of Dial. The Civil War had divided the Chastain family as it did many other families in the North Georgia mountains.

Edward and John’s mother Nancy Chastain O’Kelley (1805-1890) was first cousin to attorney Elijah Webb Chastain (1813-1874)[5]Chastain Family Ancestry – Nancy Chastain O’Kelley’s father was Edward Brigand Chastain (1769-1834). Edward’s brother was Benjamin Franklin Chastain (1780-1845) who was the father of … Continue reading of Morganton, GA. She married William O’Kelley (1795-1871) on January 19, 1826. They had at least 14 children and lost one other son during the Civil War. Nancy Chastain O’Kelley’s twin sister Elizabeth married one of her husband’s brothers–John Pendleton O’Kelley (1808-1878) eight months after Nancy’s marriage in August 1826. Both couples lived near each other in White and Hall County at the start of the war.

Nancy and Elizabeth’s first cousin Elijah Webb Chastain was one of two delegates from Fannin County to attend the secessionist convention in Milledgeville, GA in 1861. He voted in favor of secession, the other Fannin county delegate William Clayton Fain (1824-1864), a fellow Morganton attorney and neighbor, was one of the few that voted against Georgia’s secession. Soon after Georgia seceded, Elijah Webb Chastain wore rebel gray as a Colonel in the 1st Georgia Infantry. By the time of the “Incident on the Toccoa”, William Clayton Fain was dead, another victim of the chaos in the mountains, killed execution-style April 6, 1864 by Captain William Jefferson Rodgers and the seventy-five men of company D, 4th Georgia Cavalry (Avery)[6]Margaret S. McCelland Fain Widow’s Pension Application; Affidavit by Mary Catherine Slate (1837-1914) and 1864 letter by Ebenezer Fain for M.C. Briant..

But on that Friday, September 2nd, 1864 Chastain’s cousin Edward O’Kelley wore Yankee blue as he and his brother headed carefully through the woods that paralleled the north-south road that went from Dial to Morganton and then on into Tennessee.

Suddenly, in the distance, they heard the gunshots echoing along the Toccoa River.

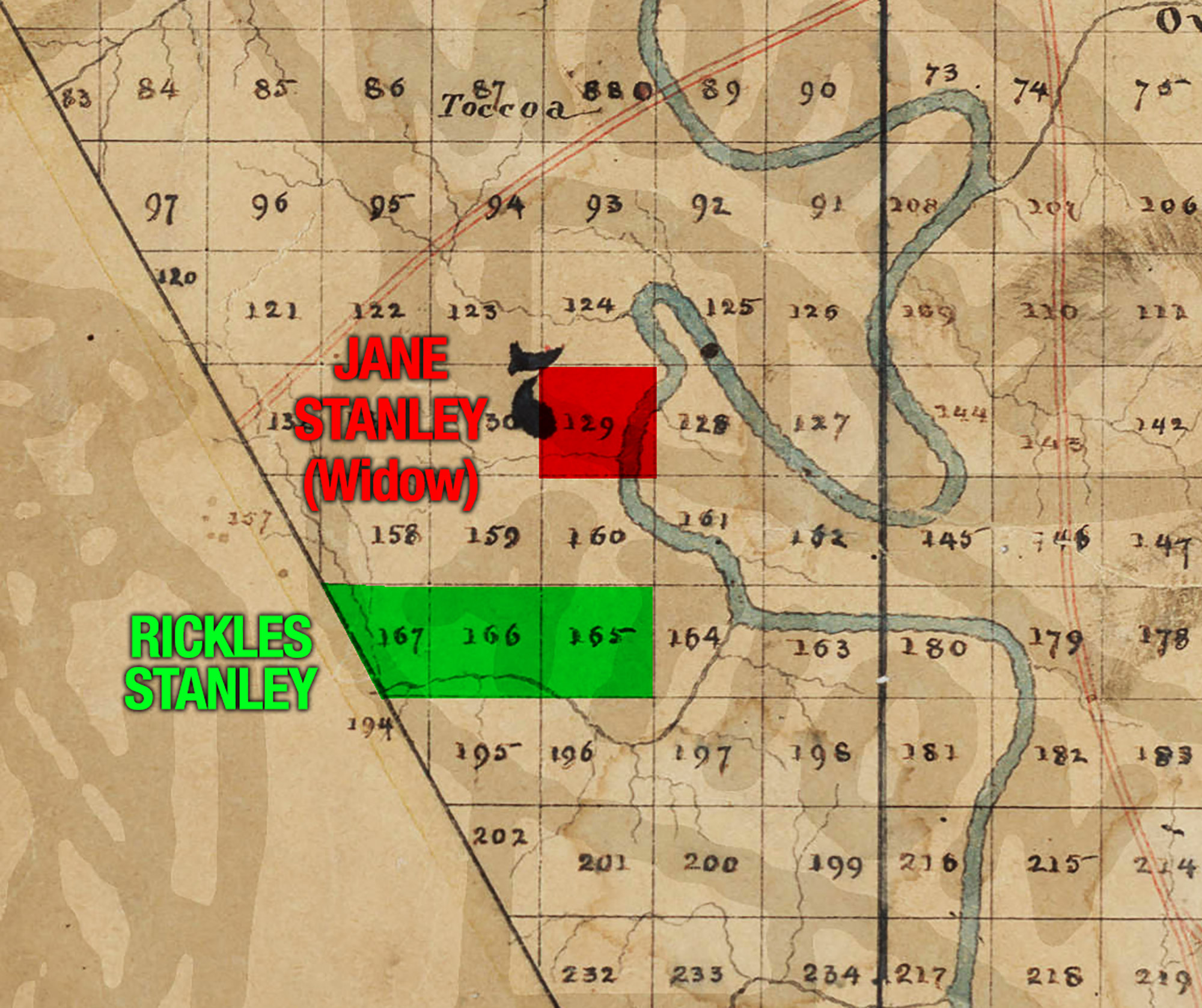

160 acre parcels originally divided in the Cherokee Land Lottery of 1832 owned by Rickles S. Stanley and Elisha Stanley’s widow Jane Garland Stanley

160 acre parcels originally divided in the Cherokee Land Lottery of 1832 owned by Rickles S. Stanley and Elisha Stanley’s widow Jane Garland Stanley

1869; Georgia Archives

The Stanley family were originally from Burke County, North Carolina and had come into the area that would become known as the Stanley settlement in the late 1840s purchasing several 160 acre 1832 Cherokee land lottery parcels from the lucky winners of the lottery. The parcels were about twelve miles southwest of Morganton which became the county seat when they carved Fannin county out of Union and Gilmer counties in 1854. Elisha Stanley owned one parcel–number 129 and his brother Rickles owned three parcels–numbers 165, 166 and 167 following the present-day path of Stanley creek as it flows into the Toccoa river as well as one parcel to the east–number 193[7]1879-1883 Fannin County Property Tax Digest. Rickles original cabin dating from the mid-1800s still stands near the Gilmer/Fannin county line on what would have been parcel number 167[8]Georgia Archives; 1869 Map of Fannin County by authority of the state; B.W. Frobel; Sup of Public Works; shows division of the county by individual Cherokee Land Lottery parcel numbers.

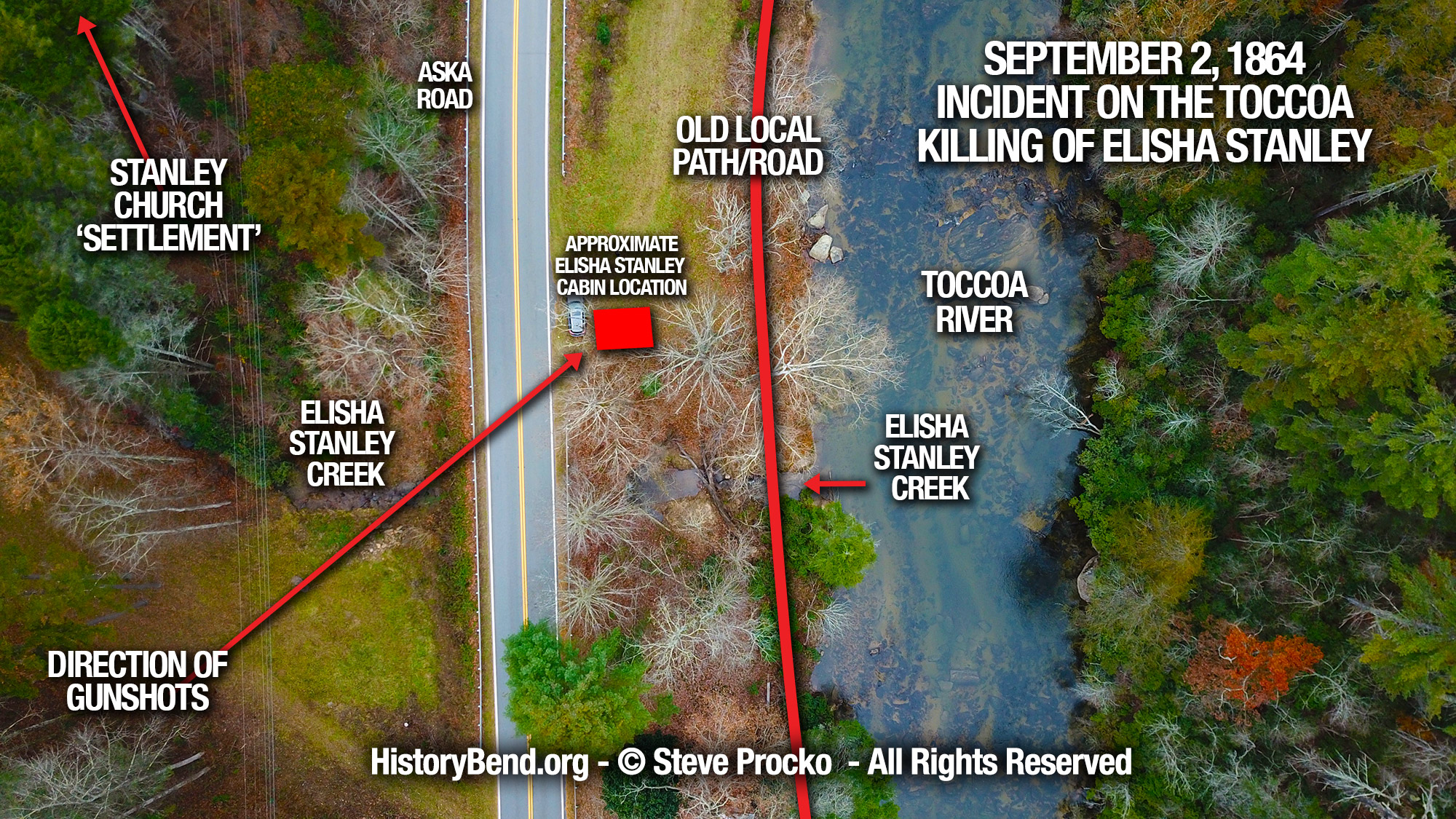

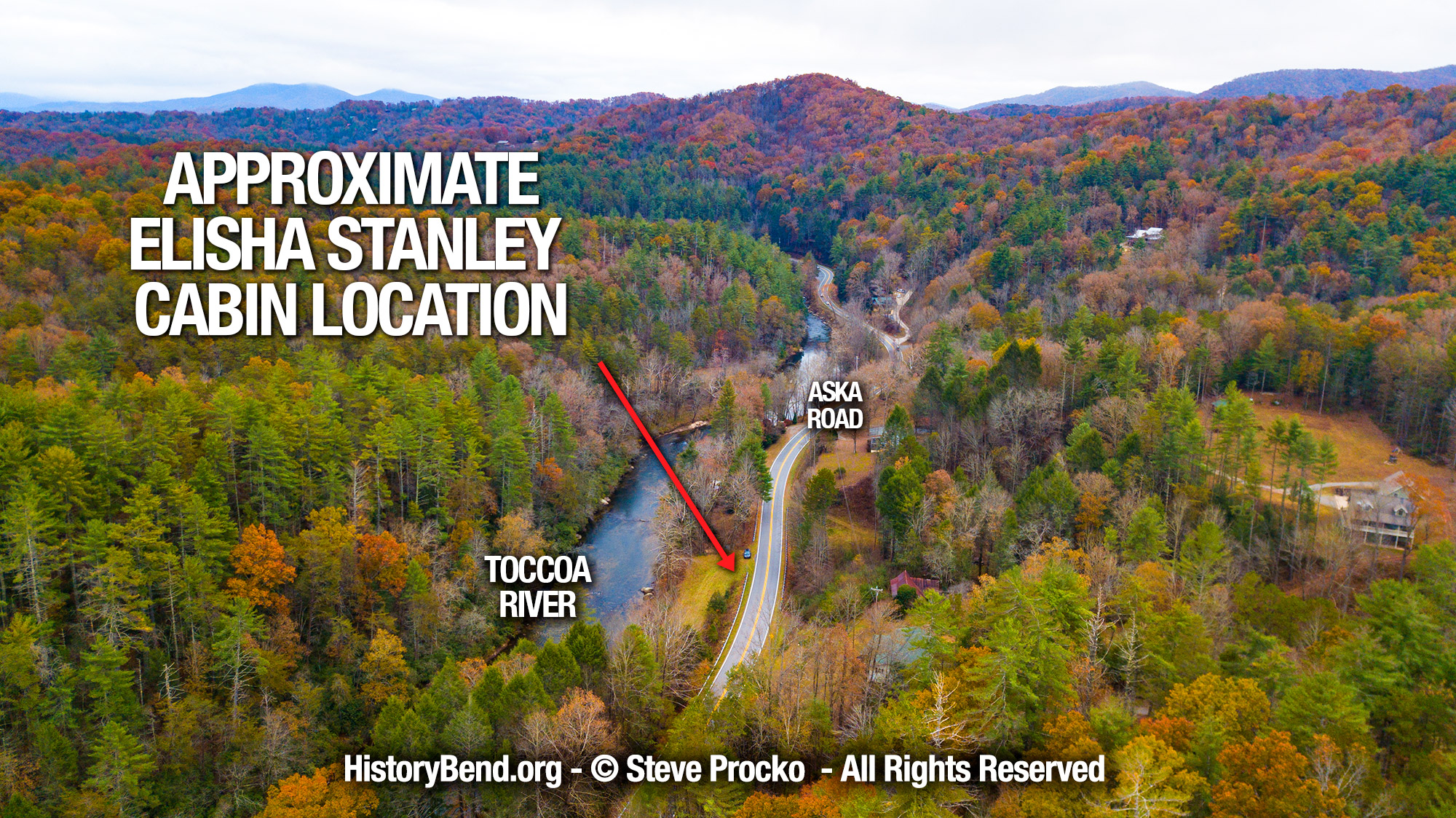

The site of Elisha Stanley’s cabin was disturbed by the building of Aska Road in the mid-twentieth century. There originally was a narrow dirt road between the cabin and the Toccoa River. The grading of Aska road completely changed the landscape of the former farmstead leaving the site unrecognizable to what it looked like over 150 years ago.

The site of Elisha Stanley’s cabin was disturbed by the building of Aska Road in the mid-twentieth century. There originally was a narrow dirt road between the cabin and the Toccoa River. The grading of Aska road completely changed the landscape of the former farmstead leaving the site unrecognizable to what it looked like over 150 years ago.

Around a bend in the river, Elisha Stanley had been sitting outside of his cabin on the banks of the Toccoa with one of his children playing nearby. Elisha was a well-known gunsmith in the area and may have been repairing a rifle at the moment the bullet hit him with a shot through the head[9]Lawrence L. Stanley, A Rough Road in a Good Land; Page 84; 1971, Craft House.. Or, in a slightly different family oral tradition, he was sitting in a chair repairing a shoe for his infant son Adolph “Buell” Stanley (1864-1943) with Buell toddling next to him[10]Ralph Stanley Interview by Steve Procko; August 17th, 2018. “Then when they shot him, all six bullets went into his chest,” said 3X great-grandson Ralph Stanley.

Around a bend in the river, Elisha Stanley had been sitting outside of his cabin on the banks of the Toccoa with one of his children playing nearby. Elisha was a well-known gunsmith in the area and may have been repairing a rifle at the moment the bullet hit him with a shot through the head[9]Lawrence L. Stanley, A Rough Road in a Good Land; Page 84; 1971, Craft House.. Or, in a slightly different family oral tradition, he was sitting in a chair repairing a shoe for his infant son Adolph “Buell” Stanley (1864-1943) with Buell toddling next to him[10]Ralph Stanley Interview by Steve Procko; August 17th, 2018. “Then when they shot him, all six bullets went into his chest,” said 3X great-grandson Ralph Stanley.

The passed-down Stanley family story continues with the detail that Buell’s mother Jane Garland Stanley (1828-1905) found Buell covered in his father’s blood.

Ralph Stanley holding his 3X Great Grandfather Elisha Stanley’s rifle

August 2018

Over 150 years after the fact, with multiple tellings of the story over the decades by family members to family members, the passed-down oral and written tradition has changed some of the particulars of the event, but the outcome was still the same.

Elisha now lay dead in a pool of blood, with gunshots riddling his body. The shots came from a stand of sorghum cane just to the west of the cabin. “The cane patch was right close to the house’, said Ralph Stanley, “It was a little yard in between and had a cane patch. From where they shot him from, my granddad said when they shot into him–and we always wondered how could they shoot that far and not miss the little boy beside of him, but they’s that good a shot’.

The six men responsible were Rebel bushwhackers were well known to the Stanley family because they were some of their neighbors. The names passed down through multiple generations were Al Brookshire, Snells Adkins, John Griffith, and men with last names of Garland, McClure and Beavers. Elisha’s wife Jane Garland Stanley came from Garland stock. So they weren’t just neighbors, they were family.

“My understanding was, Garland was the leader, said Ralph Stanley, “he was kind of the leader of the six men. It was six of ’em”.

After killing Elisha, the men continued to terrorize other members of his family ransacking the home, firing upon and shooting in the thigh Elisha’s namesake nephew, the son of his brother Rickles S. Stanley (1820-1903). The teenager would carry the bullet in his thigh for the rest of his life. Rickles’ daughter Telitha Stanley (1839-1920) was struggling to hold on to her hand-made quilt that one bushwhacker was trying to steal. The man struck her on the side of the head with his rifle butt, deafening and disfiguring her for the rest of her life.

The O’Kelley brothers found themselves in the wrong place at the wrong time as they moved towards the gunshots that had killed Elisha and ongoing ruckus. They were spotted on the opposite side of the Toccoa from Elisha’s farmstead, and the rebel bushwhackers on horseback gave chase. Two men on foot were no match for horses. Edward O’Kelley ran up the hill away from the river while John dove into the river trying to escape. The men on horseback began firing, and they hit Edward in the back. He fell where he was shot, likely killed instantly. Miraculously, John O’Kelley could escape by hiding along the banks of the river and staying under water. The O’Kelley story passed down through the family says he remained under water by breathing through a quill.

Elv Hughes execution site at the shallow ford of the Toccoa River

about a half-mile east of the bridge with the same name,

the tree now just a stump, marked by a small cross

The bushwhackers then captured Evan “Elv” Hughes, Elisha’s brother-in-law; who was upriver from where Ed O’Kelley fell. Elv and his wife Vivian “Vian” Stanley Hughes (1839-1918) were sheering sheep. They tied Elv across a horse’s saddle while his wife ran alongside, screaming and not wanting to let him go. “His wife run along, my granddad’s sister, run along holding onto the saddle, “ said Ralph Stanley, “and they kept telling her they was gonna kill her if she didn’t turn loose, too”. It was the last time she saw her husband alive. He was taken up river near the shallow ford, tied to a tree and executed. The stump of the tree is still visible just east of Shallowford Bridge on the Toccoa River. They planted a small cross next to the stump.

The Stanley’s were known “Tories” or Union sympathizers because they chose to not join the rebel cause.

When the war broke out, many of the mountain folks found a hard time supporting secession. Frankly, what was in it for them? Scratching out an existence took most all the waking hours they had and required the entire family. Very few could afford to own enslaved individuals to provide the labor. That form of farm labor was part of the lifestyle of rich folks. For the Stanley’s it was a rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight. Frankly, they just wanted to be left alone. In a time when you were marked by which side you supported, they marked the Stanleys as Union sympathizers, likely because what the confederate side offered didn’t suit their lifestyle.

Subsistence farming the difficult mountain terrain afforded the Stanley clan some security from various factions of unofficial, unsolicited militia groups who preyed upon the folks in Fannin County. Many of these groups were comprised of confederate soldiers who went AWOL and returned home to join up with militia groups sometimes referred to as “home guard” to help police their lands.

Some of these AWOL soldiers also changed sides and unofficially became members of Union-leaning militia groups policing their lands as well as “Tory home guards”. Sometimes one home guard group posed as a group from the other side making a confusing situation even more dangerous.

After the war, Rickles S. Stanley filed a Southern Claims Commission petition on July 21, 1871[11]Georgia Historical Society; Southern Claims Commission Petition by Rickles S. Stanley; 7/28/1871 to 12/5/1877. Samuel Crawford, one of his witnesses when questioned of reported threats, molestations, or injury inflicted upon the claimant, or his family, or his property, on account of his adherence to the Union cause testified, “They took nearly all his property, one of his daughters knocked down and badly hurt, his wife and other children badly abused and himself taken prisoner and put in jail”.

It was chaos in the mountains, a very dangerous time in a region very far from where the true battles between sanctioned Union and Confederate armies was occurring. But they were deadly nonetheless.

Just three months earlier in May 1864, members of the Stanley family, including Elijah and his brother-in-law Elv Hughes were captured by thirty-two-year-old Captain Francis Marion Cowan, a lawyer from Marietta who was leading cavalry company of the 1st Georgia State Line[12]May 5, 1864 account by Captain Francis Marion Cowan in letter to Governor Joseph Brown and Colonel E. M. Galt. The 1st Georgia State Line was part of Georgia’s own army raised under orders of Georgia Governor Joseph Brown. Cowan was a relative to Brown’s wife, who was given a captain’s commission and was full of great enthusiasm and zeal. Tasked to hunt down deserters, Captain Cowan charged on up into the mountains, making it all the way to Ducktown, Tennessee where he found the town deserted. The local population had clearly heard him and his seventy-five men coming. Heading back towards Ellijay, Cowan then made a raid on what was known as the Stanley settlement taking several of the men-folk prisoners, charging them with desertion.[13]Stanley names show up in the rolls of the Union 1st Georgia State Troops Volunteers under Col. James George Brown of Murray County, but they were never mustered into service. (Names listed: William … Continue reading. The Stanley’s all managed to escape after a few days. Ironically, Captain Cowan was mortally wounded and captured during the siege of Atlanta and died in a Union field hospital in Chattanooga, TN on September 1, 1864, a day before the incident on the Toccoa – he is buried in an unmarked grave.

Stanley Church where Elisha Stanley and Elv Hughes

were buried in the same grave – September 1864

After Elisha Stanley and Elv Hughes were killed, the Stanley women took on the responsibility of burying their men. At what is today Stanley Church the two men became the first burials in a cemetery now containing a great number of their descendants. Elisha and Elv were buried in a single grave, on top of each other. They were each wrapped in a homemade quilt. “Now, they buried my great-granddad and Elv Hughes in a corn box. They emptied the corn out and put a sheet down first. Laid one in. I used to know which one”, said Ralph Stanley, “ Put ’em one down, put a sheet over him and put the other one then on top of him. Not beside of him. On top of him, you know. The women did that, ’cause they wasn’t no men around”. The original marker has been replace in later years with the date of death listed as September 6, 1864. This date is likely the date of their burial.

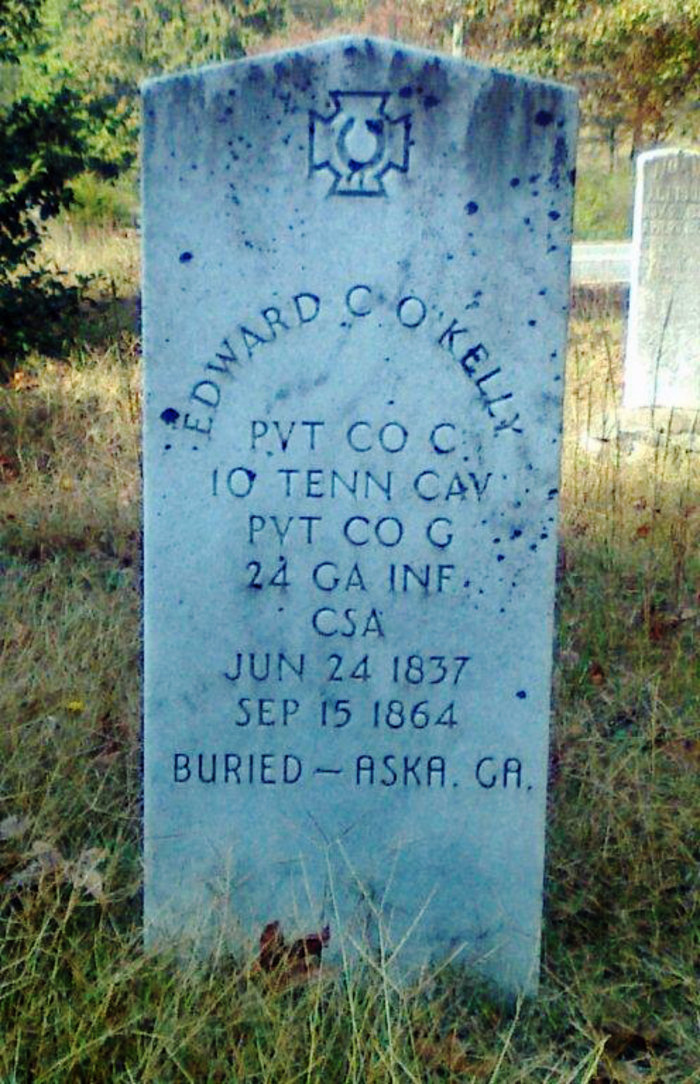

John Pendleton O’Kelley returned to the place his brother Edward was killed and found his body a couple of weeks after he was killed. His remains were wrapped in chestnut bark and buried right where he had originally fell, face down in his blue uniform weeks earlier. A simple marble marker was set at the head of the grave some years later that incorrectly records the year of his death–it reads “Ed O’Kelley Died 1865”.

Nancy Chastain O’Kelley filed for Edward’s Union army pension beginning in 1874, she was finally granted a pension in 1884 for a one time amount of $25[14]1874-1884 Nancy O’Kelley; Mother’s or Father’s Application for Army Pension. Her pension application stated that “Edward C. O’Kelley was my son and an officer in the Federal army and was killed by Rebels on his return back with recruits in Fanning [sic] Co.” However, the facts show she was in error in reporting Edward as an officer, he was just a Private.

In White county near Cleveland, Georgia at the O’Kelley cemetery where his mother is buried, a military gravestone marks the empty grave of Edward Callahan O’Kelley. It was set in the cemetery by O’Kelley’s descendant Bob Barton. The date of death as September 15th, 1864 “Buried–Aska, Ga” reflects the date used in the soldier’s pension documents from the O’Kelley family. It was also likely the day his brother John was able to return to bury the body of his brother on that secluded hillside on the east side of the Toccoa river.

After the Civil War. Elisha Stanley’s two youngest brothers Samuel Stanley (1840-1925) and William Preston “Press” Stanley (1848-1886) went after the men who killed their brother and brother-in-law. Family tradition records that retribution killings of five men occurred in the two years following the Civil War[15]Lawrence L. Stanley, A Rough Road in a Good Land; 1971, Craft House.. Press Stanley was indicted for murder in October 1867 along with Alexander P. “Pink” Collins and William Hunnicutt in Gilmer County but never tried. The newspaper of the time reported, “Civil life, receding rather than advancing during the war and reconstruction, was designed to be aided by ‘home guards,’ who were to assist the aged, the weak, and the women, if necessary, with field crops and such other tasks and duties as might aid them in living and maintaining the lines of battle. . . . But a large percentage of these so-called guards became a law unto themselves, committing so many outrages that men like Fate Sims and Pink Collins later took the lead in evening up scores”[16]Georgia Department of History and Archives; Superior Court Minutes, Gilmer County to 1900..

Soon after, Press Stanley moved to North Carolina. He never returned to Fannin County again.

FindAGrave

Edward C. O’Kelley’s empty grave in White County, GA records his service for both the Confederate and Union sides.

He died a Union private, killed by rebel home guard.

References

| ↑1 | Compiled Service Records, Company G, 10th Tennessee Cavalry (Union), Edward Callahan O’Kelley. Age 26, Enlisted 1/18/1864 for a period of 3 years in Nashville, TN. Mustered into service 2/27/1864. Present on muster rolls Mar-Apr, May-June, July-Aug/1864. Last paid April 20, 1864. He is reported as Killed in Action (KIA)A in September 15, 1864 though the place he was killed is incorrectly reported as Lumpkin County. Adjutant General’s Office, Washington, DC. 10/10/1864 officially reports him as Killed in Action. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Compiled Service Records, 42nd Georgia Infantry (Confederate), John Pendleton O’Kelley. Muster Date 3/4/1862;’ 5/15/1862 Disabled/Rheumatism; 10/2/1863 Absent, Unfit for Service |

| ↑3 | Compiled Service Records, 24th Georgia Infantry (Confederate), Edward Callahan O’Kelley. Enlisted 8/24/1862 in Whit Co., GA by Capt. Leonard. Left sick in Winchester, VA. 10/19/1862; Admitted to Richmond Hospital No. 20 10/31/1862; Appears on receipt roll for clothing 2d Division Hospital; Camp Winder; Richmond, VA 1/15/1863. No further records after that date. |

| ↑4 | Bob Barton interview by Steve Procko; June 2018 |

| ↑5 | Chastain Family Ancestry – Nancy Chastain O’Kelley’s father was Edward Brigand Chastain (1769-1834). Edward’s brother was Benjamin Franklin Chastain (1780-1845) who was the father of Elijah Webb Chastain. |

| ↑6 | Margaret S. McCelland Fain Widow’s Pension Application; Affidavit by Mary Catherine Slate (1837-1914) and 1864 letter by Ebenezer Fain for M.C. Briant. |

| ↑7 | 1879-1883 Fannin County Property Tax Digest |

| ↑8 | Georgia Archives; 1869 Map of Fannin County by authority of the state; B.W. Frobel; Sup of Public Works; shows division of the county by individual Cherokee Land Lottery parcel numbers. |

| ↑9 | Lawrence L. Stanley, A Rough Road in a Good Land; Page 84; 1971, Craft House. |

| ↑10 | Ralph Stanley Interview by Steve Procko; August 17th, 2018 |

| ↑11 | Georgia Historical Society; Southern Claims Commission Petition by Rickles S. Stanley; 7/28/1871 to 12/5/1877 |

| ↑12 | May 5, 1864 account by Captain Francis Marion Cowan in letter to Governor Joseph Brown and Colonel E. M. Galt |

| ↑13 | Stanley names show up in the rolls of the Union 1st Georgia State Troops Volunteers under Col. James George Brown of Murray County, but they were never mustered into service. (Names listed: William Sr; William Jr, Braxton, Rickles, Samuel and Elisha Stanley). |

| ↑14 | 1874-1884 Nancy O’Kelley; Mother’s or Father’s Application for Army Pension |

| ↑15 | Lawrence L. Stanley, A Rough Road in a Good Land; 1971, Craft House. |

| ↑16 | Georgia Department of History and Archives; Superior Court Minutes, Gilmer County to 1900. |